Amid a migrant crisis, Sheridan Lee speaks with two former asylum seekers about their lives in Afghanistan and journeys to Australia.

Essan Dileri, who worked in a non-governmental organisation (NGO) in Afghanistan, constantly feared for his life – and with good reason.

Humanitarians are frequently killed, kidnapped and threatened in his homeland, which has been described as “the world’s most dangerous place for aid workers”.

Dileri remembers that five of his colleagues were killed by the Taliban while working on a national solidarity program with the government.

His involvement in a government-run, alternative livelihoods project, inspired by his recommendation that poppy farmers saffron rather than opium, also placed him and his family “under great risk”. They were targeted by some of the most ruthless, ambitious and powerful drug lords in the country.

Dileri claims that “the situation was so bad” that he could not return home after a 10-day visit to present his community-based, peace-building work in Melbourne, Australia in 2009.

“If I returned home, my life would have been in severe danger,” he tells DEEP Kabul.

“There was a risk of death.”

Dileri was forced to leave his wife and two children, who fled to Pakistan, and seek asylum in Australia, as “the situation did not improve even after waiting a few months”.

“I am still not sure if it is safe for me to go back,” he says.

The fear of violence, and threat of persecution, was (still is) common in Afghanistan, particularly under the Taliban (1996-2001), who publicly beat, tortured and executed, people who disobeyed their strict code.

Humaira*, who lived in the capital city of Kabul, remembers that women were brutally oppressed by the regime.

“If we showed our skin, they would hit us. If we wore high-heeled shoes, they would hit us,” she says.

“We were very scared of them.”

Six million people are estimated to have fled the country during their five-year rule (1996-2001), and one-and-a-half million to have returned in 2002, a year after the collapse of the Taliban.

“At the time, there was a wave of hope going through the minds of all Afghans,” he says.

“We were hopeful that we would change the state of our country. There was a lot of optimism. That’s how we all went back and started life there.”

Quickly disillusioned, many fled during a 13-year war with the United States.

It is a stark contrast to Dileri’s childhood, which he describes as “pretty orderly”.

“The way that people behaved, the way that people communicated, the way that people dressed, was normal, like you would expect in a civilized society,” he says.

However, they were restricted in movement.

Former president Mohammad Najibullah introduced a national curfew, which Dileri believes was a tactic to “stop the movement of people that the government did not want to move”, like the Mujahideen.

“If you travelled at night [9pm to 4am], you would risk your life unless you were certain people, security people, who knew the password for the night,” he says.

“Society, and businesses, slowly adapted. If there was a night shift, they would have organised for people to stay over and provided them with some kind of temporary bed.”

The situation quickly deteriorated: Najibullah’s resignation after a decade-long Soviet occupation (1979-1989) plunged the country in to a chaotic civil war (1992-1996).

Dileri was deeply affected by the “inconsistency and instability” of the civil war.

“We were not sure what would happen to our country, what would happen to us, and where we would end up living,” he says.

“Any time, we could die. Any time, we could be relocated. Any time, we might leave home.”

He remembers that “several times a year, schools were closed for security reasons” and his education was severely disrupted.

“At the middle and end of the year, we would be tested on the curriculum, which we did not study at all,” he says.

“I had to work hard, and there was little support available, for me to catch up outside of school, but I was able to adapt, learn and develop that resilience.”

Dileri found some comfort in “staying home and playing games” with his three sisters.

“We learnt a lot and we laughed. These were really, really positive memories for us.”

Essan Dileri in his ancestral village. Photo: Essan Dileri, Essan Dileri’s blog.

When he returned from studying in Pakistan in 1996, Dileri found “a very different society” under the control of the Taliban.

“The city was in shock,” he says.

“There was not much hope. A lot of people were leaving.”

Humaira* also tells DEEP Kabul that it was a “very sad time” for her.

Her mother and sister were killed when a rocket hit their family home during the Taliban’s first attack on the capital city in 1995.

“Can you imagine how a teenager struggled to raise her youngest brothers? Can you imagine how difficult it is that, when you need your mother, you have to play the role of your mother for your brothers?” she asks.

After the traumatic event, she fled to her grandfather’s village in the Markazi Bihsud district of the Maidan Wardak province for safety.

Districts of the Maidan Wardak Province. Image: Rarelibra, Wikipedia Creative Commons.

“Our district [Markazi Bihsud] was not yet under the control of the Taliban, but it was still affected by the Taliban,” she says.

“They blocked our access to food, like wheat, flour and oil. We did not have oil, salt, sugar or wheat, just the harvest of our village.”

Kabul was changing rapidly.

“Men were growing very, very long beards, which they were not allowed to shave or cut, and wearing turbans,” Dileri says.

“If women were on the streets, they had to be accompanied by a male relative, a husband, brother, father or someone, so, you would hardly see any girls, or any women, on the streets.”

Women walking with their children in Heart, Afghanistan. Photo: Marius Arnesen, Flickr Creative Commons.

They were also made to wear burqas, long, loose garments covering them from head to feet, in public.

“The Taliban claim that women should cover (hijab) their whole body, head to feet, when they are going out of their home and are exposed to men who are not their close relatives,” Humaira explains.

“If a woman’s beauty is apparent and not covered, it will arouse and motivate men’s sexual enthusiasm, and this is a sin.”

Humaira, who returned to Kabul to visit a doctor, was “very careful” to wear a burqa.

“I had never worn a burqa before that,” she says.

“We did not have to wear scarves, we did not have to wear burqas, but when the Mujahideen came to power, we had to wear scarves, and when the Taliban came to power, we had to wear burqas.”

Girls’ schools were also shut down. Humaira was denied the right to an education.

“I always prayed and wished that the Taliban would leave Kabul, so I could go back to school,” she says.

Humaira started to “write her feelings on paper” because she “could not share [her] feelings with anyone in [her] village”.

“Most of the women were illiterate, so when I said that I missed school, they did not understand me,” she says.

Her family fled to Pakistan for the sake of their education, but returned after hearing that “the Taliban had been overthrown by the American troops”.

“It was like a revolution,” she says.

“We were hopeful that we could access schools, work, jobs and everything, so it was very good.”

Humaira was still “thirsty for education” and “enthusiastically searching for a scholarship to study in a high-ranking university and in a developed country”.

“At the time, I was offered a scholarship from the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA),” she says.

“I chose to study in Australia [in 2012] because it has a good image in my country: it is a well-developed and multicultural country.”

After graduation, Humaira “searched, and applied, for jobs, but got no response.”

“It is difficult to get an office job here, especially when you are not a permanent resident or citizen,” she says.

“I do some volunteering work in my spare time to return part of the resources that are invested on me to the community and other people.”

Adel*, Humaira’s husband, recently arrived in Australia on a visa.

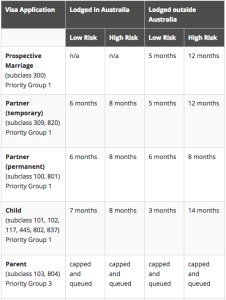

The Department of Immigration and Border Protection details the “[projected] service standard processing times for people wanting to migrate on a family stream visa”, like Adel, on their website.

Family visa processing times. Image: Department of Immigration and Border Protection website.

Kon Karapanagiotidis, founder and CEO of the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre (ASRC) in Melbourne, tells DEEP Kabul that family visas are rarely processed within the projected time frames.

“On average, the wait is three to eight years.”

He believes that former Immigration Minister Scott Morrison’s decision to reduce the country’s refugee intake by 31%, from 20,000 to 13,750 people annually, over the 2013-2017 period, has significantly worsened “wait time blow outs”.

“Our government time frames are [now] so poor and our placement numbers are [now] so small,” he laments.

“Most are only going to be granted a temporary protection visa for three years, and then have to reapply, only to be granted another temporary protection visa.

“During this time, they can not sponsor, or be reunited with, their families, so they are separated from their parents, their husbands, their wives, their children.

“So, from the time that they arrive here [Australia], to the time that they are granted permanent residency and have the right to sponsor their families, it could be an 8-10 year wait.”

It is a “long, drawn out process”, which can have a profoundly negative impact on an asylum seeker.

“When you are separated from your family, particularly during the formative years of your children’s lives and your relationship, you can imagine the devastation that it is going to cause on the family unit,” Karapanagiotidis says.

“How does your marriage survive that? What do children do without their parents?”

Dr Nicholas Haslam, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Melbourne, agrees.

“Uprooting and separation from loved ones is a key factor in their emotional distress,” he says.

Dileri, who endured a three-year long wait to be reunited with his wife and two children, also describes it as a “difficult and lonely” experience.

“It was very, very challenging being away from my family.”

As he waited for them, he searched for employment.

“I thought that it would not be difficult for me to find a job because I know the language and I have a degree, but it was very difficult,” Dileri says.

“I would apply for a position and not receive a call back. I would receive an automated response, like ‘thank you for your application’ and ‘we will get back to you’.”

Karapanagiotidis admits that it can be difficult for asylum seekers, like Dileri, to “get their skills recognised”.

“Bridging courses are costly, which can drive people in to lower skilled jobs and lead to higher rates of depression and social isolation.”

A psychiatric study from the University of Melbourne has revealed that sixty percent of asylum seekers living in Melbourne experience major depression.

Associate Professor Suresh Sundram, who was involved in the study, has even coined the term ‘prolonged asylum seekers syndrome’.

“We have talked about this syndrome before but it is becoming increasingly clear that it appears to be distinct from anything else that we have been seeing,” he told the ABC in 2012.

“They are particularly vulnerable [to depression].”

During his stressful experience, Dileri battled with depression.

He believes that his family “kept him going and helped him to get out of that circle of depression”.

“If I stayed in that circle, what would have happened to them?” he asks.

“I am the only son, so my family and my parents depend on me.”

Forming friendships, exercising, volunteering, visiting a local library and talking to the librarian, and finding a job, were also crucial to his healing process.

Dileri was offered the role of program coordinator for Voices for Change, a project of the Spectrum Migrant Resource Centre (MRC) in Preston, Melbourne, in 2011.

“It was very similar to what I did in Afghanistan,” he says.

“In Afghanistan, we worked on a program called ‘youth out of conflict’, which helped young people at risk of becoming disengaged. We focused mainly on counter-extremism.

“So, given my experience, I applied and they [Spectrum] offered me the role.”

Dileri was quickly promoted, moving from Team Leader for Youth Services to Program Coordinator for Settlement and Family Services in the same year.

In every position, he seeks to “make a difference in someone’s life”.

“It is quite empowering to work with people who are vulnerable, who have some sort of disadvantage,” he says.

“It can be quite taxing on you and them but, at the same time, it is very rewarding to see that you have made a difference in a person’s life.”

Dileri, and his friend Jill Parris, wrote about his life experience in Raised in Conflict, which he launched in 2013.

“It was a therapy for me,” he says.

Essan Dileri and Jill Parris. Photo: Essan Dileri, Essan Dileri’s blog.

Dileri wanted to share his story to reflect, inspire and teach.

“When I grow older, I can go back and cherish those memories,” he says.

“I thought that it could be a source of inspiration for people. It could also be a lesson for people in prosperous parts of the world to see and experience the lives of ordinary people living in situations of conflict.”

Dileri believes that every government has a responsibility to share the burden of the migrant crisis in Europe, described as the region’s worst since World War Two.

“In democratic and civilised countries, such as Australia, we must do whatever we can to help these people, to provide them with safety and shelter,” he says.

Dileri views the decision of the Australian government to permanently resettle 12,000 refugees from Syria as a “really positive move”.

“But, as a nation, we could do more, we could definitely help more people to settle in Australia,” he says.

If you would like to purchase a copy of Raised in Conflict, please contact Essan Dileri directly.

If you or someone you know requires assistance, contact Lifeline on 131 114 or beyondblue on 1300 22 4636.

Sheridan Lee is a second-year journalism student at La Trobe University. You can follow her on Twitter here: @sheridanlee7.